How To Win At Life: Unexpected Life Lessons From 31 Meters Under The Sea

I am on a small, open boat, racing across the Adriatic Sea, as Croatia’s charming shoreline buildings start to appear smaller and smaller.

No, I’m not in a James Bond movie.

The way I appear is far too unglamorous for that.

My eyes are squinted–not in the sexy, I’m-doing-this-on-purpose way, but in the crap, this-salty-ocean-water-keeps-getting-into-my-eyes-and-burning way.

I’m involuntarily flopping about, in a different direction, with each wave the boat hits.

And my eyebrows and mouth are unknowingly fixed in such a way that I’m sure clearly communicates my concern with my potential to plop off this boat and into the Adriatic.

Despite the fact that I am not alone in this boat, I do seem to be alone in my concern for my ability to stay in it.

Everyone else (all white men) is sitting calmly, chatting with one another, enjoying the breeze and the ocean spray as we go further and further out to sea.

I’m the only (black) one with the appropriate facial expressions, muscle tension, and prayer muttering for the situation, if you ask me.

Pride is the only thing stopping me from leaning onto the person next to me, wrapping all my limbs around them, and clinging to them for dear life.

But if we hit another good wave, my pride may just give out.

It never ceases to amaze me to see the comfort level of white people as it pertains to the potential of unexpected falls into cold water.

I mean, we’re about to go on a dive, but still, I don’t want to be in the water any sooner than planned or necessary.

Good thing we have these seatbelts…

This feels like a good time for me to tell you that the “seatbelts” on the boat are thin leather straps that you tuck your toes under.

I have $9 sandals from the discount bin at Ross that provide a greater sense of security.

The more I travel, the more impressed I become at how liberally people use the term “seatbelt” (with a straight face) to describe things that are supposed to give you a feeling of safety.

But, today is a good day.

Today, I’m going to dive a shipwreck, as one of the required dives to earn my deep dive certification, that will allow me to access dive sites deeper than my open water and advanced open water certifications will.

PSST – Before we continue…

This article was brought to you by…knowing how to swim…without that ability, I would not have been able to dive, which has now become one of my favorite things to do. In my book, Challenge Accepted, I talk about 15 life lessons I gained from doing my impossible and learning how to swim as an adult. It’s equal parts laughs (at me and with me) and aha moments, and you can buy it on Amazon.

But I am not just diving any shipwreck.

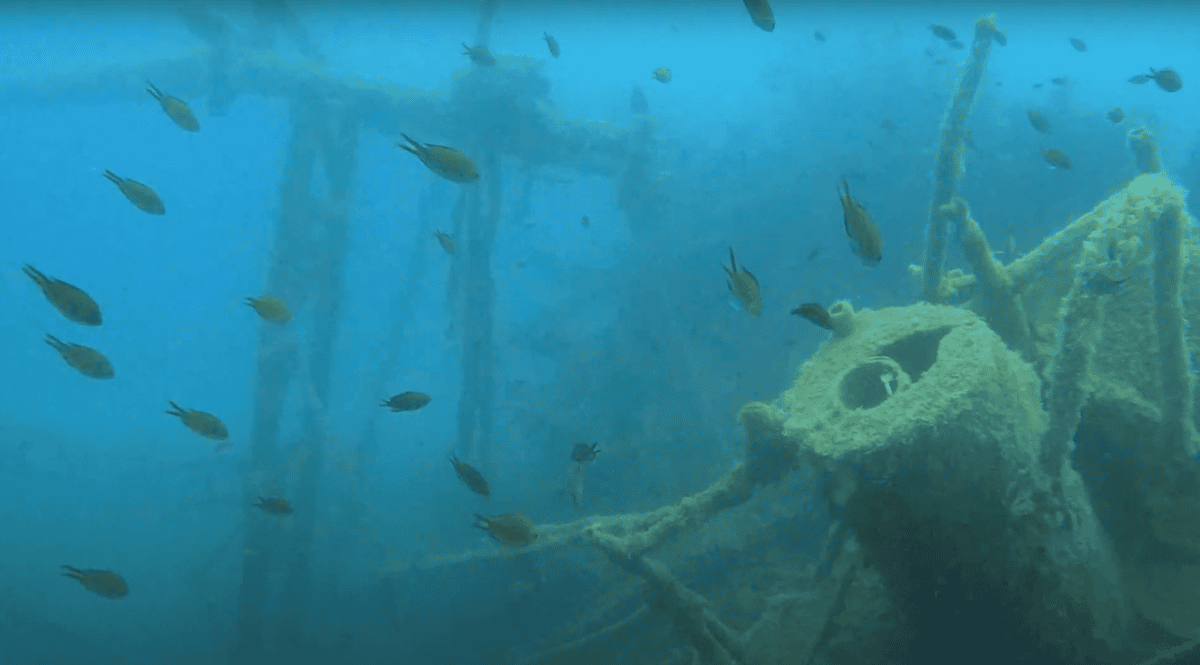

I am diving the Baron Gautsch.

Known as the “Titanic of the Adriatic,” it was a passenger ship that sank in the early 1900s when it hit a mine, and claimed over 100 lives.

I have dove several shipwrecks before, but this is the first one I will dive with casualties.

So, something that I usually approach with sheer excitement and joy, this time I am approaching with more reverence and humility.

I have mixed feelings, as we often do when life inevitably reveals to us its dichotomy and presents to us situations that trigger both sadness and happiness, that are both unsettling and peaceful, and that turn tragedy into beauty.

It was both a sad and beautiful reminder that no one thing is singularly bad or good.

And this grave at the bottom of the sea, now covered in coral and inhabited with marine life, is a reminder that out of death comes life.

Mixed feelings around today’s particular dive site aside, scuba diving has become one of my favorite experiences, favorite excuses to travel, and now, after having done dozens of dives, one of my favorite recurring hobbies.

Each dive gets you a front row seat to the indescribable wonder of nature–you’ll witness hundreds of different species of aquatic creatures, with their vast array of shapes, sizes, colors, patterns, and textures, and see the varied and interesting ways they move through the water and interact with each other.

I’ve been surrounded by tens of thousands of tiny fish, glistening and sparkling under the moonlight, I’ve been circled by giant manta rays, and I’ve found myself swimming with schools of colorful fish that looked like they were from a Disney movie…

It’s very exciting but it also brings such peace.

It’s a peace that doesn’t just come from the physical experience of weightlessness from being underwater.

Once underwater, I love looking back up to the surface and seeing just a rising trail of bubbles from the air tanks of divers, sometimes the kicking legs of swimmers if it’s a shallower dive, and the distorted image the moving water creates of the surface world.

It’s not what I see up there that gives me peace, but what I don’t see.

With the obvious physical and visual separation between the world I am in now, and the world I came from, comes a mental and emotional separation from the problems and worries I left behind on the other side.

But that peace is not just automatic.

That whole weightlessness feeling is something you do have to kind of work at.

Scuba diving is one of those things that looks easier than it is.

Strap a tank on your back and just float underwater, point at the fishes and go “oooh ahhh”…how hard could it be, right?

But, there’s actually quite a bit more to it than that.

The deeper you go underwater, the more the pressure increases, and the more adjustments you need to make to your body and your diving equipment to compensate.

And you are constantly changing depths and moving shallower or deeper all throughout the dive.

This means that instead of just pointing at the fishes and going “oooh ahhh”…you actually have a little bit of homework to do underwater.

You have to “equalize” continually as you go deeper to make the pressure in your body and the pressure outside your body the same, in order to avoid that head exploding feeling.

This is done by usually pinching your nose and blowing out of it simultaneously, or just swallowing.

This has to be done every few feet or every meter or so as you descend.

Then there’s this little thing called buoyancy.

Perhaps the biggest challenge of them all.

If you don’t properly control your buoyancy, you will either sink towards the bottom or float towards the surface.

If you do properly control your buoyancy, you will feel like you’re weightless, and look like you’re perfectly, effortlessly floating in the exact same spot underwater.

As you go deeper in water, air pockets in your body and in your diving equipment shrink in size, making you less buoyant, and making you naturally sink more easily.

As you move up into shallower waters, air pockets in your body and your equipment expand, which makes you more buoyant and naturally float more easily.

So in order to make sure you control being at the exact depth you want to be at at all times, you have to constantly add or subtract air by using your breath in your lungs and/or inflating or deflating your BCD (the vest you wear to dive that’s connected to your air tank).

This manual manipulation controls the depth at which you float in the water, and is necessary in controlling your descent as you begin a dive, ascent as you end a dive, and navigation during the dive.

It is also necessary to work around the current as it changes in the water, and to avoid obstacles that come up in the water.

Here’s the trick…just as in life, when you make a change, you don’t get an immediate result.

If you inflate your BCD or inhale, you don’t instantly go up.

There’s a delay.

So you have to make small adjustments and be patient to see their result before making rash changes.

And you have to see something coming in the water, and make a change before you get to it.

So as you can see, there’s kind of a lot going on.

Diving isn’t just a hobby–it’s a skill.

A skill that (until today), I thought I was never going to really get comfortable with.

I would always look at more experienced divers underwater with envy.

They had perfect control over their descent, ascent, body movement, were able to maintain the coveted, sometimes elusive “neutral buoyancy” that is the “nirvana” for scuba divers, and they did all this while also recording videos and being perfectly calm.

Meanwhile, I’m frantically fiddling with all my bells and whistles, internally beating myself up for “not doing it right,” and wondering if anybody else is feeling this same current pushing me around that I feel.

Sometimes I feel like I’m in a different ocean than the guy right next to me.

The peace that I experience when first beginning a dive can quickly dissipate as my frustration mounts at my inability to dive as well as the other divers I’m with.

What I thought would be an innocent, fun hobby, turns out to have just enough variables to drive an overachieving perfectionistic overthinker like me crazy, and just enough things to doubt my aptitude over.

As if I didn’t have enough of that in my life on land.

But today, I had a mindset shift.

And as a result, I was calmer, and had my best dive yet.

I finally felt like I got it.

Today, I realized that the skill in diving isn’t being able to just magically float perfectly the whole time.

The skill is in being able to make adjustments calmly, quickly, and intuitively in order to get yourself back to equilibrium.

The best divers are so good at making adjustments and they’re so unfussed about it, that from the outside, you can’t even tell that they have forces working against them.

They make it look like everything is going perfectly smoothly for them.

And that’s not the case.

It’s just that they make adjustments perfectly smoothly.

They’re not great divers because they’re diving in perfect conditions.

They’re great divers because they are able to perfectly adapt to imperfect conditions.

Your success in life doesn’t come down to being granted ideal circumstances.

Your success in life comes down to your ability to adapt in less than ideal circumstances.

When I’m diving with other divers, we’re all working with the same unpredictable, adverse conditions–the currents, the cold, the bulky equipment…

The people I looked at with envy who were the best divers were the ones who were able to best adapt to the environment, and with the best attitude.

They are the ones who anticipate obstacles and adjust themselves before reaching them in order to avoid them altogether.

They are the ones who make subtle changes calmly, instead of rash changes frantically.

They are the ones who work with the environment, instead of fighting against it.

They don’t fight against the current–they either flow with it and use its momentum to propel them in the direction they want to go, or move out of it so it doesn’t take them away and get them too far off their path.

They don’t panic if something doesn’t go exactly according to plan.

If they get water in their mask, if their mask gets knocked loose, if something gets caught on their BCD…

They don’t gripe about it.

They don’t freak out about it.

They don’t cancel the whole dive.

They simply adjust from where they are.

You can’t always run away from your problems.

Sometimes, you have to deal with them from right where you are.

Perhaps, best of all, the best divers don’t fail to recognize the beauty and amazement all around them despite the unfavorable conditions.

And further, they don’t compare their experience negatively to others’.

They don’t complain that the group that dove before them saw a gigantic fish and they didn’t.

They’re grateful for having the chance to dive at all, and although their experience was different than someone else’s, they still enjoy and appreciate it for what it uniquely is.

And sometimes conditions change.

Maybe earlier in the day, conditions were easier.

The divers who went earlier perhaps had calmer seas, warmer waters, better visibility…

And now on your dive, conditions are worse.

What would a good diver do about that?

Complain that someone else had it easier?

Or do the best they can to adapt around the conditions they have to work with right now?

(Hint: the answer is option 2.)

Every dive always starts with a clear plan.

But you must be flexible on how to execute that plan based on the conditions.

The plan is to make your way from the start of the dive site to the end of it, and have as much fun as you can enjoying the journey in between.

But just because you have a destination in mind doesn’t mean you can just make a straight beeline from point A to point B.

The path isn’t going to be laid out perfectly smoothly for you.

You will find fish, rocks, and coral that you will have to go around.

Sometimes, you will have to go up first to make your way down, or go down first to make your way up.

You’ll encounter current that will move you in one direction and you’ll have to adjust accordingly.

Then the current will change in a different direction, and you’ll have to adjust again.

You can’t control everything about your outside environment.

You can only use the tools and tactics at your disposal to make the best of what is happening around you to stay on your path, or at least get back on it when you are pushed off of it.

You can only do the things that are within your control to make the best of what is outside of your control.

You can’t control everything about your external circumstances.

You can only control yourself within those circumstances.

What will you change about yourself to get what you want?

What will you change about your approach to get what you want?

How will you adapt to your circumstances as they are–not how you want them to be–to get what you want?

External circumstances are not always going to be favorable to you.

They’ll constantly change, they’ll be uncomfortable, they’ll knock you around in directions you don’t want to go.

But what you do about it is what determines your success or failure in the end.